Hammering Through the Ages

Tucked away in the tiny town of Acquaviva, a barn-sized workshop seems as quiet and non-descript as the other buildings. Yet, within the shop’s walls, a centuries-old profession is still in full swing.

The occupation of blacksmith, beginning so far back in time that the actual date of its start is unknown, is upheld today by Roberto Zepponi. Machinery and a wide array of tools are strewn about the shop, waiting to be used for the next ambitious project.

In the dusty workspace, the orange glow of the fire and red-hot iron illuminate the blacksmith’s face as he molds his next creation. The clanging sound of metal against metal  echoes throughout the workshop as 39-year-old Vincenzo Zepponi, cousin of Roberto, repeatedly pounds metal on an anvil to make the perfect curlicue for the end of a rail. Under Roberto’s direction, Vincenzo helps add to the decoration of the surrounding towns through the balconies, railings, gates, and other metal works the shop has produced. echoes throughout the workshop as 39-year-old Vincenzo Zepponi, cousin of Roberto, repeatedly pounds metal on an anvil to make the perfect curlicue for the end of a rail. Under Roberto’s direction, Vincenzo helps add to the decoration of the surrounding towns through the balconies, railings, gates, and other metal works the shop has produced.

Today, they are constructing a grand balcony in a process that could take three to four days to complete. Each piece of the balcony has to be perfectly formed to match the others, and each also takes a great deal of strength and patience to create.

With the same painstaking precision and care practiced by blacksmiths of long ago, Roberto Zepponi brings today’s pieces of metal to life.

It might be presumed that such a trade is handed down from generation to generation, but Roberto Zepponi’s father was a truck driver, not a forger of iron. Zepponi first became involved with iron work at a vocational school, where he specialized in operating a metal lathe. He did not really have a choice in the school he went to, and said that he just sort of “fell in” to this area of craftsmanship. Luckily, he realized he liked working with metal from the very beginning, and it eventually grew to become a passion.

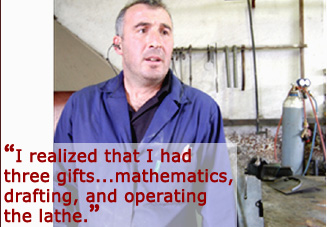

“I realized that I had three gifts as a young man,” Zepponi says. “Mathematics, drafting, and operating the lathe.”

He began his work in 1979, at the age of 22. Before becoming a blacksmith, Zepponi played for the Cagli soccer team for three years and continued to spend seven more years on the team even while pounding iron by day. Now, at 51, he works with Vincenzo and others to create iron daily.

He is drawn to the idea of taking simple pieces of iron and from them, creating useful objects. The traditional method of iron work is what captures his interest the most; this method does not involve welding, but instead uses nuts and bolts to hold the pieces of iron together. “Real iron work,” Zepponi comments, comparing it to the more cost- and time-efficient process of welding.

Though the workshop is equipped with the modern technology essential to a safe work environment for a blacksmith, injuries are still likely to happen. Along with the normal burns and cuts, Zepponi suffered a serious injury when a sliver of metal flew off the metal lathe and into his right eye. As a result, his vision was slightly damaged. Another memorable injury of Zepponi’s came from a metal saw, which left a large scar on his middle finger.

Tools of the trade

A workday for Zepponi typically consists of at least eight hours, and the intense labor and long hours are beginning to take a toll on him. The high decibel sounds from the various machines, along with the hammer striking the anvil, are already affecting his hearing, even though he and the other workers almost always have plugs in their ears. When they’re not inserted, the protective devices, attached to cords, hang around the workers’ necks like doctor’s stethoscopes. the other workers almost always have plugs in their ears. When they’re not inserted, the protective devices, attached to cords, hang around the workers’ necks like doctor’s stethoscopes.

Clients of Zepponi come from all over the region. One of the shop’s biggest projects was a palazzo (palace) in Cagli that has between 30 and 40 apartments, for which he created the balconies and internal stairways.

He takes great pride in the fact that he has never advertised his work, even with the shop being located so far off the beaten track. “The prices are honest, and the work is good,” Zepponi says, chuckling. “Otherwise, the customers wouldn’t come looking for us.”

In addition to Vincenzo’s assistance, Zepponi has one apprentice who has been working for him for a year. In the past he has taught his trade to four workers, with the last one opening his own shop after three years of working for Zepponi.

Zepponi has two children: 21-year-old Nicola, currently at the university, and 27-year-old Linda, who carries on Zepponi’s artisan skills by painting ceramics. Zepponi is proud that his daughter, like himself, uses her talents and love of art to form beautiful creations out of simple, everyday objects.

“Our pleasure doesn’t come from commerce,” he says, sliding his protective goggles back on his face. ”It comes from creating.” |