The Changing Face of Italy

Immigrants pour in searching for new opportunities

Visuals and text

by Lara Aqel

Looking back on a life of hardship, disappointment, and unrelenting work, Fatima Mochtare pauses before a smile of resignation moves across her face. "I would do it all over again for my family," says the 52-year-old Moroccan woman.

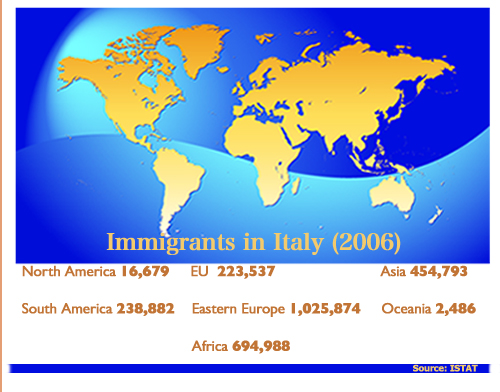

Mochtare, who works as a live-in housekeeper for an aging Cagli woman, is part of a wave of immigrants changing the face of Italy. By the end of 2006, the Italian government had documented almost 350,000 legal Moroccan residents, the second largest group of foreigners in the country. Officials estimate twice as many Moroccans are in the country illegally.

Historically a nation that has exported its population to the rest of the world, Italy has found itself absorbing an influx of immigrants from North Africa and Eastern Europe over the past two decades. According to The International and European Forum of Migration Research, a combination of events has made the country a prime destination for immigrants. Italy's shrinking native population has resulted in a high demand for workers at the same time other nations are closing their borders. And Italy's decision to grant amnesty to illegal immigrants five times between 1980 and 1990 has only made the nation more attractive to the wave of North Africans seeking better economic lives.

Fatima Mochtare is part of that wave.

Born in the "white city" of Casablanca in 1955, she graduated with a bachelor's degree in literature in 1976, yet the best job she could find was secretary at an automotive firm.

But even that pay wasn't enough to help her parents support their family of 10 children. So in 1981 she headed for Italy and the hope of higher pay.

"The eldest always has a noose tied around her neck, pulling along everyone else behind her," says Mochtare with a small laugh that does not make it all the way up to her dark, doe eyes.

Claiming there was no need for visas back then, she relates the story of how a 72-hour car drive with a friend, her friend's husband, and son, through Spain and France, brought the four of them to Italy and landed Mochtare in Lecce, the Italian town she lived and worked in for 18 years.

"I worked two jobs, one during the day and one at night. Babysitting, waitressing, cooking, housekeeping, homecare: I did everything I could do."

Having learned French during her school days in Morocco, she became fluent in Italian after only three months with the help of a French-Italian dictionary. In 1990, Mochtare was legalized in one of the amnesties the Italian government granted illegal workers. That year, she also gave birth to her first and only child, a boy named Zachariah.

When Zachariah was two years old, she sent him to live with her mom and sisters in Morocco.

"The old women [she cared for] don't tolerate your having a baby at your side," she says, touching the one picture she has of the boy.

Currently Mochtare cares for Maria Teresa Urbinati, an elderly Italian woman with a heart condition, whom she calls "Mama." She lives in the woman's dining room while providing round-the-clock care. "She only has me, and I only have her. She is a very tired woman. She needs me," Mochtare explains, sympathy furrowing her brow and lighting her eyes.

She has little time for friends and explains she would have a hard time making them in Cagli. Foreign workers in Italy are often the recipients of hostility and resentment from the famously hospitable Italian people, who argue that foreigners are taking Italian jobs, committing crimes with impunity, and upsetting the social structure of the country. However, the Italian Social Security Archive's analysis of data on foreign workers has found the presence of large numbers of foreign workers almost exclusively in Italian regions with low native unemployment and high excess demand for labor.

The impact of immigration has even been felt in Cagli. Government statistics maintain that there are 93 legal Moroccan residents in Cagli, along with 115 Albanians, 56 Chinese, 41 Macedonians, and 36 Ukrainians, among others. The illegal workers are not officially accounted for.

Mochtare admits that there is a social divide between the foreigners and the natives in Cagli. One of its most obvious manifestations is the difference in materialistic values between the two groups. Italians put much importance in their culture on the concept of belle figure, or good appearance, and subsequently spend a considerable amount of income on looking well-dressed.

"They see you not dressed [well], and your hair not done, and they don't speak to you. We [foreign workers] don't have the money to spend on designer clothing. What's important to us is that we live and that our families live."

After more than 20 years in Europe, Mochtare continues to reflect on those she left behind. Having already lost one member of her family, her father in 2004, Mochtare is determined to reunite with her son who is graduating from high school this year.

Mochtare hopes to bring him back with her to Italy in July and have him enroll in a local university. Ultimately, however, she hopes for the two of them to return to Morocco.

"I will stay five more years and return to Morocco. I want my own house so my mom and son can live with me, and so my three younger sisters can get married," she says.

![]()

For more information: