|

by Lauren O'Connell by Lauren O'Connell

Andrea Pellegrini knows the mountains of Cagli so well that he could navigate their trails blind. In fact, he once did. When a dense fog descended during a hike, Pellegrini managed to follow his own tracks back to safety. As a licensed nature guide, the 34-year-old has spent years studying and exploring the mountainous terrain in Cagli and the surrounding region. He is deeply passionate about his work. For Pellegrini, love for the land is more than just his job and more than just an interest. "It is a mission," he says. He is determined to teach others to respect and appreciate nature, just as he does. As he sees it, his work is crucial both to his future and to the future of Cagli.

Pellegrini came to Cagli in 2004 after moving around the region six times in 10 years. He sees familiaritywith the entire area as an essential element of his work. |

If you want to know a territory very well," he explains, "you have to experience it." Thus, this native of Urbino has traveled extensively throughout the Appen ine Mountains of Italy's Le Marche region. ine Mountains of Italy's Le Marche region.

Aside from the course he took to become certified as a nature guide, Pellegrini is self-taught in his craft. He is the secretary of the regional chapter of the Guide Ambientali Escursionistiche (GAE), a national association that attracts hiking enthusiasts, which works to organize guides and develop tourism in the country. Pellegrini has written a book and is co-author of several others. His time is divided between guiding mountain tours, speaking to local students about his work, writing and researching as well as exploration.

Pellegrini relishes the time he spends alone in the mountains, traversing uncharted regions with his camera and binoculars. "For a guide, it is very, very important to know not only the paths," Pellegrini explains, "but the entire area." In keeping with his immersion philosophy, Pellegrini makes his home in a small village nestled on the slope of Monte Nerone, one of Cagli's three mountains. There, he has been busy observing the amphibious life. Pellegrini's book, Monte Nerone: Nel Regno della Salamandria tells the tale of one particular amphibian that is unique to Cagli, an endangered species of salamander that is found on Mount Nerone. |

"The salamander is a good biological indicator," says Pellegrini. "If the land is not polluted, it can survive." But as the naturalist has observed, both the salamander's survival and Cagli's hang in the balance.

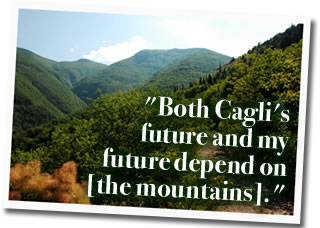

Pellegrini says much of the history of Cagli is written on its terrain. It is a checkered past of human impact, staged beneath the shadow of the mountains. Two groups make their home atop the city's green peaks: those who harvest the land for farming and woodcutting and the monks who leave the land around them untouched. While woodcutting has decreased in recent years, those who remain in the mountains must attempt to live in harmony with nature to preserve their way of life, he argues. Like the salamander, however, the traditional lifestyle that once thrived in the mountains has become endangered. Pellegrini's village, once home to many families, has dwindled to a population of only four. Pellegrini says much of the history of Cagli is written on its terrain. It is a checkered past of human impact, staged beneath the shadow of the mountains. Two groups make their home atop the city's green peaks: those who harvest the land for farming and woodcutting and the monks who leave the land around them untouched. While woodcutting has decreased in recent years, those who remain in the mountains must attempt to live in harmony with nature to preserve their way of life, he argues. Like the salamander, however, the traditional lifestyle that once thrived in the mountains has become endangered. Pellegrini's village, once home to many families, has dwindled to a population of only four.

As Pellegrini explains, the threats for mountain-dwellers are great and numerous. "Wild animals can destroy the agriculture, and the wolves can kill the animals," he says. This costs the farmers dearly, driving many off the land. Perhaps the greater danger is neglect that has brought much of the mountain lan d to ruin. Not many laws exist to regulate human use and misuse of the mountain terrain. "Few people in Cagli and this region know [the mountains very well]," Pellegrini laments. d to ruin. Not many laws exist to regulate human use and misuse of the mountain terrain. "Few people in Cagli and this region know [the mountains very well]," Pellegrini laments.

"In Italy we have a problem," he says, "we have so many monuments that some monuments [are broken and many are not restored]." Thus, Cagli's mountain monastery has fallen into disrepair. Museums displaying fossils have closed. Pellegrini says he believes that the mountains and the importance of the environment do not get adequate attention.

Pellegrini has a plan to save Cagli's mountains and the lives of those who make their home there, if anyone is willing to listen. |

"I think the only hope for this place is a national park, because a national park can be a project, a real project for the future," says Pellegrini. "Without a national park we have not many tourists, but we have many problems." A park would draw tourists, providing a new source of strength and income for Cagli's economy. It would provide much-needed protection for the mountains' monuments as well as its inhabitants and their traditional lifestyle. Most importantly, he says, a park would preserve the land that Pellegrini loves so dearly, from the tallest tree to the smallest salamander.

Unfortunately, Pellegrini says, many people in the region fear tourism, not understanding that newcomers could, in fact, help to preserve the lifestyle of the region. "Sometimes the people who know me say that I have a good job. Other people say that I am crazy," Pellegrini says. Yet he is willing to do whatever it takes to get his message out. His latest project, a book about the birds of Le Marche, is a personal production. He hopes that an organization will publish the work once it is completed. Pellegrini thinks that this costly and time-consuming effort is a risk worth taking if it means protecting the terrain of his beloved homeland, Le Marche.

Pellegrini's message and goals are simple. "Underline the importance of the mountains," he says. "Both Cagli's future and my future depend on [them]." |

Photos by Elizabeth Samolis

Video by Katherine Harrington

Web Design by Alli James |

| [HOME] |

|

|

|