Story by Lauren Hicks

It is noon on a typical Armagh weekday, and the sun is making its sporadic appearance. The townspeople bustle around for lunch, and in the background you hear the single peal of a bell, one that promises more to come.

Not to disappoint, a shower of sounds rains down from the heavens, threads of loveliness at once happy and mournful, offering no choice but to stop and listen. Once the last drop of music is drained from the skies, you sigh in appreciation and continue the day. The bells of St. Patrick’s have finished their performance.

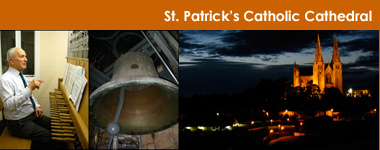

What you may not know is that this city is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland. It hosts two separate St. Patrick’s cathedrals, one Catholic and one protestant, hence two sets of bells. The Church of Ireland perches atop Sally Hill parallel to Vicar Hill while the Catholic cathedral looks out from Sandy Hill on the other side of town. Both churches are recognized as ecclesiastical seats of the Anglican and the Roman Catholic faiths in Ireland, with the heads of each church positioned here. The dual cathedrals make Armagh a unique and historically captivating town.

Close Encounters with Carilloneurs

Baron George Minn is a retiree who can often be heard playing the bells at the Catholic cathedral. An organist from Belgium, he has been the town carillonneur since his move to this Northern Ireland city in 1959. Minn braves the 105 steps that lead to St. Patrick’s magnificent bell tower to play hymns as well as a few favorite songs: The Bard of Armagh, My Lagan Love, and Harvest Dance. As the bells and chimes ring out, he smiles and his booming voice can be heard exclaiming,

“C’est magnifique!”

Carillon bells are a group of at least 23 bells of different weights and profiles. Each bell is composed of 78% copper and 22% tin, but the metal composition is adjusted slightly to give each bell a unique sound. The heaviest carillon bell weighs over 24,000 pounds while the smallest weighs just 17 pounds. A carillon commonly plays melodies and tunes, because of the quickness of the sound and the range of bells. The carillonneur uses his fists and feet to hit the a piece called the clapper. This is attached to a keyboard, or clavier, and moves to strike the bell, creating a scale of heavenly notes. The sound can be slightly “clangy,” perhaps even considered out of tune because of the unusual melodic characteristics of the foundry bells. Imagine a “ding-dang ding-dang” sound that rings from the bell tower down through air.

The Bells of Change Ringing

Just a few moments’ walk away on neighboring Sandy Hill is the Protestant Church of Ireland and Mr. Sean McCabe, a part-time verger. McCabe attends to some of the church’s needs and possesses a particular passion for ringing. But instead of a full carillon, there are only eight bells that float in the eaves are rigged so that they can swing freely, ideally in a complete 360-degree circle. Rather than play tunes, the bells are rung in patterns, called “changes.”

Change ringing uses far fewer bells than a carillon but still emits a scale of sweet sounds. Instead, the bells are rung in precise relationship to one another. Each change involves a precise mathematical pattern that relies on timing as the essential element. The ringer uses a flicking motion with his hand to pluck the wires and sound the bells. The notes in a change tend to last longer so the sounds layer upon one another for the full effect. This resonance leans more towards a deep “doooonnngg, doonnnngg,” depending on the size of the bell.

Up the stone stairs and along the beams of this Church of Ireland, it is possible to feel the cold of the oldest bell, dating from 1721, and also to get a peek at the newest bell still shiny from 1885! A proper change bell is mounted on a wooden frame, allowing for a delicacy in sight and sound that is rarely enjoyed these days.

There is never an hour of the day when Armagh city residents do not hear the melodious tunes of the bells. Historically, bells were rung to gather the townspeople together.

In modern times, one hears the Catholic St. Patrick’s cathedral chime at least every quarter hour (using an automatically timed ringer), while the protestant St. Patrick bells characteristically ring before Sunday services, as well as on important occasions.

George Minn, for example, often plays for weddings, while Sean McCabe has rung the bells on momentous occasions, such as the Queen Mother’s death, and in commemoration of the victims of 9/11 (when the bells were rung 50 times). With all the strife and conflict Armagh has experienced, it must have been difficult to imagine a day when Catholics and Protestants could co-exist peacefully in the same town. Today, however, the wounds are beginning to heal.

Minn and McCabe, who both exude a deep humility than can’t properly be expressed, are one subtle yet immensely moving reminder of the quiet strength building in Armagh. Both men become enraptured in the sound of each chime and express nothing short of pure affection for the melodious bells. They look after their charges and care about the story behind them. Sean McCabe has even helped to repair bells in both cathedrals.

To hear a melody ring out at half past five or before celebrations on a Sunday morning may not appear highly significant to an outsider. But to the faithful, each set of bells in Armagh has become beautifully symbolic, unique voices with depth, history, and a message.

Story by Lauren Hicks

Photos by Kyle Saadeh

Video by Janine Quarles

Web Design by Felicia Chapman

|