Beyond the Brogue

Life as a minority in Armagh

Inventory is finished. The kitchen is clean and stocked. He checks the locks one more time, looking out the restaurant window at the now darkened streets. Such calm can be deceiving. As a man of color and Muslim faith, he knows better than to go out at night. No use worrying about it now, though. He walks upstairs to bed.

Polish residents of Armagh at The Indian Tree.

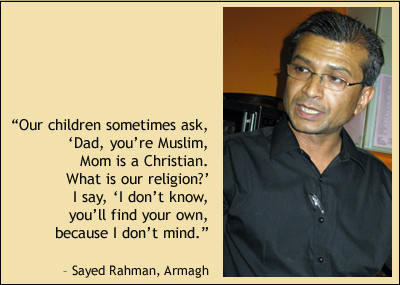

Polish residents of Armagh at The Indian Tree.Sayed Rahman ends another day in Armagh, the ecclesiastical capital of Northern Ireland. Why is Armagh the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland? Two cathedrals, one Roman Catholic, one Protestant, tower over the tiny town beneath. Though they’re beacons of belief and sanctuary to most, these houses of worship remind Rahman, who is from Bangladesh, that his faith, his heritage, will forever be foreign.

“Somebody asked me, ‘Are you a Catholic or a Protestant?’ I said, ‘I’m a Muslim.’ The man said, ‘A Catholic Muslim or a Protestant Muslim?’” Rahman recalled, shaking his head in wonder. “He knows only Catholic and Protestant or nothing. He has no idea about other religions.”

With Protestants claiming around 53 percent of the religious population of Northern Ireland and Catholics claiming the remaining 43.8 percent (wikipedia), residents of other faiths and backgrounds can be left largely unacknowledged, claims Nisha Tandon, project officer of ArtsEkta, a Northern Ireland arts organization dedicated to the needs of artists among ethnic minorities.

“I think it’s important,” Tandon said. “Many areas, even in Belfast, don’t believe in minority diversity. It’s either Catholic, Protestant or they’re done. But to me that’s not diverse.”

Rahman believes it should be the responsibility of city leaders to help foreigners integrate into a community, and feel welcome. Tandon agrees, adding that Armagh should have a database documenting the numbers of minorities, both ethnic and religious.

Rahman is the owner of The Indian Tree, one of two Indian eateries in Armagh. Prior to taking ownership of the sit-down restaurant in July, Rahman owned an Indian take-away shop in Omagh, where his wife and two sons still live. It was also in Omagh where he learned the price of being different.

"In the last five years I've been attacked maybe three or four times, some of them violent, some of them verbal abuse," Rahman said. "Once in Belfast, they threw a bucket of ice at my car windshield. Even in Omagh, normally what happened was verbal abuse."

Rahman’s take-away shop was located next to a pub, which lead to most of the verbal abuse and harassment he endured, he said. Such verbal abuse ranged from shouts of “Hey, Bin Laden” and “Give me a Hammas kebab,” among other offensive epithets. His shop window was broken three or four times in three years. Last December, a man kicked him as he walked to his car.

“I don’t know why he kicked me. He just said, ‘What? Black bastard.’ Sometimes they’d buy food from us and shout, ‘You f***ing black bastard,’ and throw it in our face,” he said.

Rahman said he had enough of such behavior and eventually sold the take-away business. His current establishment brings “gentler people,” most of whom sit in to eat, he said.

“Even our customers in Omagh, 95 percent are good,” Rahman laughed. “Five percent are troublemakers. But that 5 percent make lots of trouble.”

Since becoming owner of The Indian Tree in Armagh just a few weeks ago, Rahman has not experienced such harsh treatment. But he believes this change is mostly due to the kind of restaurant he works in, rather than a change in the residents themselves. He and his friends still do not feel safe going out at night.

“Some people, if they are racist, they don’t say anything, which is good – as long as we’re not abused,” Rahman said. “But I have been so many places, so many countries, and only in Northern Ireland do I feel discriminated against. Maybe they don’t like foreigners.”