Story by Kyle Saadeh

Imagine you are a devoted Christian monk living in 9 th century Armagh. After doing the morning chores and prayers, you sit beneath an oak tree to eat lunch and review your studies. The weather is chilly, but not unbearable, and in the distance you can hear the ping of metal against metal as the local blacksmith hammers away at his latest task. The trees rustle with the strong Irish breeze, and slowly you drift into slumber. You are suddenly awakened by the distant screams of villagers running for their lives.

The year is 832 A.D., and the Vikings have come to Ireland.

Bolting up, you run into the chapel and up the tower, where you can see the entire town and surrounding area. Looking north toward the Blackwater River, you see smoke rising from the hills. Another scream catches your attention, and you look down the hill. Half the town is burning; people are fleeing into the hillside from their homes carrying all their belongings. Warriors are making their way towards the chapel; they have long red and blond beards, wear shiny helmets and chest protectors, and carry war axes that gleam in the sun. Panicked, you run into the basement and barricade the door behind you - bracing for the worse. Bolting up, you run into the chapel and up the tower, where you can see the entire town and surrounding area. Looking north toward the Blackwater River, you see smoke rising from the hills. Another scream catches your attention, and you look down the hill. Half the town is burning; people are fleeing into the hillside from their homes carrying all their belongings. Warriors are making their way towards the chapel; they have long red and blond beards, wear shiny helmets and chest protectors, and carry war axes that gleam in the sun. Panicked, you run into the basement and barricade the door behind you - bracing for the worse.

The Conquering of Armagh

The Norse chieftain Tuirgeis of Norway has landed in Éire. His plan is to establish a pagan empire worshipping the ancient Norse gods. Tuirgeis will make himself lord of the Emerald Isle. He concentrates his efforts in the north, coming with a great fleet of 120 ships, which hold some 12,000 warriors.

Tuirgeis himself leads the conquest of Ulster. He and his men take possession of Armagh, Ireland's most holy city, which contains "the staff which Christ himself was said to have gifted to St. Patrick," according to Seumas MacManus' History of the Irish Race. Tuirgeis drives away the abbots and converts the church of Armagh to a pagan temple while anointing himself high priest. By 845 A.D., however, Tuirgeis is murdered - some say the Irish King Malachy of Meath imprisons and drowns him in Loch Owel, while others recount how Tuirgeis is ambushed when Malachy's daughter made a tryst with him, accompanied by fifteen young Irish warriors disguised as maidens. After Tuirgeis' death, the Vikings abandon their settlements, move up the Shannon, and head to the Sligo coast where a fleet carries them home.

Hidden Perspectives

Ireland's history, riddled with war, insurrections, and invasions, contains episodes of lesser known strife. The Viking incursions are an example.

Long before land disputes with Britain and internal religious struggles, Ireland was besieged and terrorized over several centuries by the Norsemen - Swedes, Norwegians, and Danish warriors who sacked the major cities of Ireland - Dublin, Limerick, and Waterford, for example.

The Vikings were ferocious and extremely skilled. Being master boat builders, the Vikings were among the most mobile peoples the ancient world would ever see. Their long narrow ships carried Viking men and women to parts of the Mediterranean, to Greenland, and to parts of North America. Around the 8 th century, wealthy Vikings started to branch out and explore much of Europe; in the search for bounty, they plundered indiscriminately. Their mobility allowed them to perform hit-and-run raids, a unique tactic that baffled their enemies whose defenses revolved around long sieges. One can imagine how terrifying it would have been to wake up one morning to see Viking ships coming through the morning fog.

The Vikings first came to Ireland in the late 8 th century. They landed on Rathlin Island and soon set up ports and bases all over the Eire, including Dublin, Cork, and Limerick. By the 9 th century there was a sizeable Viking encampment in Lough Neagh, just north of Armagh. From the lough they sent out raiding parties through most of present day Ulster. Monks in St. Patrick's monastery atop Sally Hill in Armagh (now the site of the Anglican St. Patrick's) first recorded the Viking incursion around 832 A.D.

Stating that the "foreigners" came and plundered three times in a period of just a month, historian and curator of the Armagh County Museum, Dr. Greer Ramsey, asserts that for the next 150 years the Vikings would come to Armagh periodically to plunder the town and chapel for silver, wine, food, and prisoners - who were usually traded throughout the corners of mainland Europe for more silver (the most desirable precious metal for Vikings).

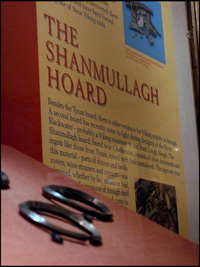

For many years historians debated whether the Vikings were ever in Armagh. But in the early 1980s Northern Ireland saw some of the worst flooding in years. A huge project was undertaken to dredge the Blackwater River and to dump the removed riverbed over nearby fields. At first only a few Viking artifacts were found, but soon the townsfolk brought out the metal detectors, and archaeologists, including Ramsey, discovered a sizeable number. For the next ten years many significant artifacts were saved from the bottom of the river and, therefore, oblivion.

Part of this collection, called the Tynan Hoard, is now held in the Armagh County Museum. The surprisingly pristine condition and elaborate designs of the silver bracelets the Viking warriors wore is a testament to their ability as craftsmen and metal workers. While the reason so much priceless treasure reached the bottom of the river remains a mystery, it is not hard to imagine the Viking raiders making use of the Blackwater River's close proximity to Armagh and its potential as a quick escape to the Viking safe-haven in Lough Neagh.

All this begs the question: Why would the Vikings (who were primarily seafaring people) come to Armagh - a relatively isolated and land-locked area of Ireland? Armagh lacked any natural or human resources of significant interest or strategic importance. "To understand why the Vikings would come to Armagh, you would have to understand the significance of St. Patrick's Cathedral," Dr. Ramsey observes. Armagh was (and still is) considered the ecclesiastical center of Ireland, and ever since St. Patrick decided to build his first church upon Sally Hill in the middle of the 5 th century, Armagh has been the undisputed the epicenter of Christianity in Ireland.

By the 9 th century the Catholic Cathedral in Armagh had accumulated vast amounts of wealth. To a pagan, who had no moral qualms about plundering such a holy site of its wealth and people, Armagh's spiritual significance meant nothing. The fact that the Vikings treated Armagh as though it were an ancient ATM machine (plundering it as much as three times in one month) is evidence of the extensive wealth held in Armagh.

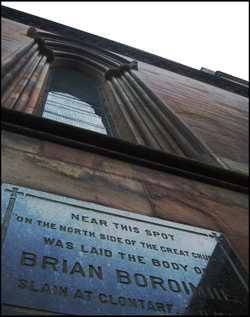

Brian Boru Defeats the Vikings

In one ironic twist of fate, the same wealth that doomed Armagh to Viking incursion helped fund the armies of Brian Boroimhe (Boru) - the famous Irish king who defeated the Viking armies at the battle of Clontarf. King Boroimhe aligned himself with the Armagh clergy, and in return for their monetary support named Armagh the religious capital of Ireland. To this day, visitors to Armagh can find a plaque on the side of St. Patrick's Cathedral on Sally Hill marking the spot where King Boroimhe's body is rumored to be buried.

Since their ships first landed on the shores of Ireland, the Vikings have influenced and shaped the course of Irish history and culture. Along with establishing major ports that eventually evolved into some of Ireland's major cities, the Vikings brought with them their ship-building skills (a trade that became a pillar of the Irish economy for many years), along with new techniques in metalworking and weaponry. Dr. Ramsey points out that, "one of the most significant contributions to Ireland is the introduction of coinage to the country." The Vikings who were not killed or did not flee the country, biologically dissolved into Ireland's people - leaving behind their genes. The iconic Scandinavian Titian-blonde hair and tall muscular build can still be seen in many modern day Irish.

Even to this day, in the city of Armagh, you can see and feel the impact of Tuirgeis and the Norse. If you climb to the top of Sally Hill where St. Patrick built his first church, and listen to the wind, you might hear the clank of Viking metal as the warriors marched down the hill - leaving the scent of fear behind them.

Story by Kyle Saadeh

Photos by Lauren Hicks

Video by Felicia Chapman

Web Design by Janine Quarles

|