|

Back from the Troubles: Cathy Rafferty Makes Good

By Caitlin Robirds

Busy at the bar with her regular customers, Cathy Rafferty, owner of Rafferty’s pub in Armagh, greets customers with a warm and friendly hello. She has dark brown hair with blond highlights, piercing blue eyes, and a welcoming Irish accent.

She also has a resume worthy of a modern woman. Rafferty is a successful Armagh business woman and a former IRA activist and prisoner. Now an Armagh city councilwoman, Rafferty is trying to foster community in Armagh and restore peace within it. She typifies the “new Armagh,” remembering how easily a society can be divided and trying to find ways to promote greater tolerance and to improve relations among townspeople.

Chequered Past

Cathy Rafferty has seen more than most will ever see in their lifetimes. Born in Armagh, she grew up as the third eldest in a working class family of six children. Her parents struggled at times to make ends meet. Cathy grew up in a modest one-room house with an outdoor toilet. She remembers that at that time her parents were simply trying to keep six children fed. Her father was Protestant and her mother was Catholic, giving them some protection from the political turmoil. In her neighborhood, if people were not loyalist supporters, she noted, British troops “searched everybody’s house very forcefully and brutally.

“Catholics were considered second class citizens,” Rafferty continued. Inequalities in employment and housing opportunities produced a conflict over civil rights in Northern Ireland. During that period schools had little money to provide an adequate education for all, especially for economically deprived Catholic children. Therefore, Cathy was forced to grow up quickly. She left school when she was nearly15 years old. Working in a knitwear factory, she made children’s jumpers and garments.

Making of a Rebel

Having endured so much trauma at a very young age, Rafferty began to rebel. She became active in the protests that were occurring throughout the city. Witness to violence and brutality most of her childhood, Cathy Rafferty was deeply affected. “At the age of 13 or 14, it is very influential on you,” she said. The brutality of the troubles caused her to join the Irish Republican Army (IRA), which was fighting for a unified Ireland against British rule.

At the age of 17, Cathy and her 16-year-old sister Edna had become part of an IRA operation that led an attack on a British soldier, leaving him wounded. Cathy thinks about the incident nearly every day; she’s grateful that nothing worse happened. “It was the wrong thing to do, but at that time in your life, you are so influenced [by outside forces],” she said.

Shortly after, Rafferty and her sister were brought to the Armagh Women’s Prison awaiting trial. Because her sister was so young, however, she was not convicted and was allowed to return home. Cathy Rafferty remained. Most political prisoners were left awaiting trial for up to18 months before ever being convicted of a crime. Eventually Rafferty was convicted and sentenced to six years in jail for her involvement in the shooting.

During the troubles, many IRA members were protesting unfair conditions in prison. Many political prisoners took part in “no blanket” and “no wash” protests, which meant they refused to wear prison uniforms, using only blankets to cover up. At times, the prisoners refused to shower or bathe; they believed they were owed certain rights such as regular clothing and educational materials. Instead, prison officials treated the IRA members exactly the same as common criminals, murderers, and thieves. The overall treatment sparked massive demonstrations in prison.

Rafferty was forced to make a decision that still haunts her to this day. Her father had been diagnosed with cancer and would not live for much longer, but if she took part in the protests, months and even years could be added onto her sentence, making it even longer until she would be able to see her dad. Reluctantly, Rafferty followed the advice of her family and began complying with prison laws. She did not partake in the no-blanket, no-wash protests. However, her father passed away during her jail sentence. Fellow IRA members were supportive of her choice not to take part in the protests. By 1981, Rafferty was released.

Click here for a tour

of the Armagh Women's Prison.

Councilwoman, Bar Keeper, Peace Maker

Today, Rafferty says she has moved on. But she hasn’t forgotten the troubles or how much Armagh has progressed. She and her husband Bernard now own one of the oldest and most successful pubs in Armagh, Rafferty’s, which was originally established in 1901. The couple bought the bar in 1985 from its prior owner and recently renovated it. They now live happily in Armagh with two children and a dog.

Among her many duties of wife, mother, and business woman, Rafferty has added a city council position to her list. At first reluctant to run, she yielded at the urging of her peers. She says she still feels guilty about not partaking in the IRA prison protests, believing that representing the townspeople today can help make up for it. “Being a councilwoman is something I felt I needed to do,” she said.

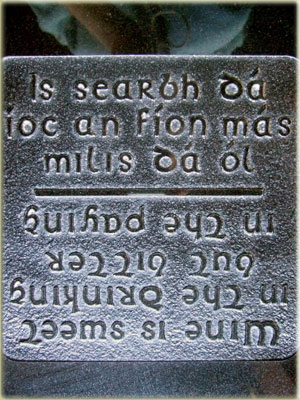

Rafferty adds she is indifferent to religion today and doesn’t care whether someone she meets is Catholic or Protestant; she simply wants what’s fair and right. Her pub is welcome to anyone with a friendly face and open heart. Some Protestants regularly venture into the pub, feeling even more welcome and safe than in pubs in their very own neighborhoods, she said.

Story by Caitlin Robirds

Photos by Brigid Carey

Video by Juanita Dudhnath

Web Design by Christine Doughty |